🤝 Navigating the IP Labyrinth: Insights from Tai Nahm

An IP Lawyer's Strategies for Navigating Rights and Innovation

I'm thrilled to bring you this exclusive Q&A with Tai Nahm, a distinguished figure in the intellectual property (IP) law arena. With over two decades of experience, Tai has established himself as an expert IP lawyer, P.Eng., and registered patent and trademark agent, dedicated to guiding startups and multinationals through the complex world of IP rights. His career is marked by significant achievements, notably at his own practice, NAHM IP LAW, where he provides strategic insights on acquiring, managing, and leveraging IP to drive innovation and growth.

Tai's journey is not just a testament to his expertise but also to his passion for transforming theoretical concepts into protective legal frameworks that empower inventors and creators. Our discussion with Tai delves into the intricacies of IP licensing, offering a roadmap for navigating and securing intellectual property in the competitive tech landscape.

1/ Tai, from your 20+ years in IP, what's the first thing a founder should consider before diving into IP licensing?

The topic of IP licensing could easily take up an entire book, but let me try to cover a few basic things to keep in mind, specifically in the context of copyright and patent licensing. When founding a start-up company and trying to get it off the ground, I think it’s important for founders to realize that they won’t have time to create everything from scratch, even if the founder and their team are perfectly capable of doing so. Given limited time and resources, founders have to decide what their core skills and capabilities are, and prioritize their valuable time on setting strategic goals for their business and working to achieve them. A part of this strategy may involve licensing-in third party technology when in makes sense to do so.

Here are some situations when licensing third-party technology may make sense.

If the founder needs to bring an MVP to market as soon as possible, licensing-in third party technology can greatly reduce the development time and facilitate earlier market entry. Rather than building technology from scratch, which may require significant resources and introduce a high degree of risk, licensing-in certain technologies may help greatly reduce cost. For example, if you need to build an IoT device for your MVP, working with an established custom dev shop to provide a basic platform upon which you can build your proprietary technology, and a license to use any necessary background IP incorporated into that basic platform, can get you to market much faster.

Another situation in which it may be more cost effective to license technology is if the technology area requires specialized expertise. If there are experts who could do a better job in a fraction of the time, seek out their expertise so that you can focus on your core mission for your business. This may allow you to quickly access tested and proven technologies, which may significantly reduce risk. But one thing to keep in mind is the potential risks of licensing in technologies when you don’t understand the licence. For example, some open source software (OSS) licenses include provisions that require you to disclose the source code for any modifications you make to an OSS module, effectively rendering your work public rather than proprietary as you had thought. So you also need a plan on how you and your team will manage the OSS licenses if you intend to make use of them to save time and development costs.

In short, the founder should focus the company’s resources on its core competencies, and concentrate on what they do best. Licensing-in technologies that are not a core competency can streamline operations, and allow you to achieve greater efficiency in creating and delivering value.

2/ You've got a ton of experience with start-ups and multinationals. What are the common pitfalls you see founders make in the IP process?

The most common pitfall that I see is when founders do not think about developing an IP strategy at the outset, with the key objective of protecting all of their innovations to create value for the company and all of its stakeholders. A first step is to get familiar with all of the different types of IP tools that are available to protect a company’s assets, including patents, designs, copyright, trade secrets, and branding. This should be followed by an IP audit to see what IP assets a company has or will be creating, and how to best protect these assets. Once you’ve identified the company’s IP assets and thought about how you can protect them, you can create an actionable IP protection strategy to create value within the company. [For our Canadian readers] Currently, there are many great resources that you can tap into, including a number of Federal and Provincial programs, including Elevate IP, IPON, and NRC-IRAP delivered through IPIC, each of which have IP education programs available exactly for this purpose.

3/ Could you break down the patent licensing process in layman's terms? How does a founder go from initial conversation to licensing?

A first consideration is whether you need a patent license, and in some cases, if you are incorporating some industry standard technology protected by standard essential patents (SEPs), you may have no option but to take a license. This is the case for many wireless technologies, and technology in specialized fields such as video compression standards and audio processing, for example. Typically, for industry standard patent pools, licenses are available on a FRAND (Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory) basis, and taking a license may be mandatory to do business in the technology field.

In other cases, it could be a single patent which may be blocking your entry into a market, and taking a license may allow you to gain entry. In this case, the licensing process typically begins with an initial conversation between the patent holder and the potential licensee. The parties can discuss the terms of the license, including the type of license (exclusive, sole, non-exclusive), the scope of the licensed rights, royalty rates, and any other relevant terms and conditions. Once the parties reach an agreement, the terms can be formalized in a patent licensing agreement.

In some cases, you may be licensing a bundle of IP rights including some patents, or even pending patent applications covering the technology, and in this case you need to understand what is being licensed, and when it would be appropriate to modify or terminate the license, for example if a patent application never issues to patent because the claimed subject-matter is deemed not patentable. If you are licensing an issued patent, you would of course take into account the life of the patent, and when it expires. So it’s important to think about how a license may end even as you are just entering a patent licensing agreement. You should also consider allocation of risk, and request an indemnity from the licensor for the technology being licensed, in the event that it may infringe third-party IP rights.

4/ What’s your take on navigating IP in different international markets? Any quick tips for founders looking to go global?

One thing to keep in mind is that “global” IP protection is very expensive. I always advise founders to develop a pragmatic IP strategy with their business goals and IP budgets in mind. If a company’s key markets are the U.S. and Canada, filing for IP protection (patents, designs, trademarks) just in these two jurisdictions may make sense. If a founder is looking to go overseas, then consider ways to defer costs, for example by filing an international PCT application which can delay the time for entry for up to 30/31 months from the earliest priority date. This can buy an additional 18/19 months of time within which to get some traction in the market, and determine which jurisdictions to enter the National Phase. Even then, this should only be done with a strong business case for each jurisdiction you wish to enter, given the significant costs of filing, prosecuting, and maintaining patent rights in each jurisdiction.

5/ How do you help start-ups evaluate whether their idea is patentable or not? What's that process like?

I typically start with a quick Patents 101 session to explain the key criteria for patentability – novelty, utility, non-obviousness, and patent-eligible subject-matter – that a patent examiner applies when assessing whether or not to grant a patent. I then explain how the examiner applies one or more prior art references to challenge patentability on the basis that the claimed invention is not new, or that the claimed invention is new but would be obvious to someone skilled in the art. I then explain a step-by-step process for comparing all of the features of an invention against the known prior art to identify the key features or functions that can differentiate the invention from the prior art, either in a single prior art reference, or in any combination of two or more references. The more key features or functions you can identify that can differentiate your invention from the prior art, the better the chances of successfully obtaining a patent. I’m happy to go into further detail on this on a one-on-one basis, but let’s leave it there for now for the sake of brevity.

6/ When a founder's ready to license IP, what are the key steps they should follow to make sure they're getting a fair deal? How should they value the IP?

For standard-essential patents or SEPs, there will usually be a license available on a FRAND basis, and generally these licenses will be fair in the sense that everyone will get the same licensing terms, although some may get more favourable terms for higher volumes, or if they hold one or more of the SEPs. For other patent properties that you would like to license as a one-off, it’s important to try to get a sense of what the patent license is worth by getting assistance from a patent lawyer and a patent valuation expert.

Valuing a patent is not a straightforward exercise, and many factors can come into play in establishing the value. But logically, a patent will have less value if the scope of the patent claims are narrow such that they can easily be circumvented. A patent will have more value if its claims cover a core technology or innovation that you must have in order to get into the market, especially if the patent has been litigated in court and has been found to be valid. This is why some of the most valuable patent properties in the world are pharmaceutical patents that claim specific pharmaceutical compounds or formulations, method of synthesis, method of use, dosage, and/or delivery modes as a way to achieve an effective monopoly. In this case, a “fair deal” may be just being able to get a license in the first place. The bottom line is that a “fair deal” is whatever makes sense for your business, and whether the license allows you to achieve your business goals and objectives.

7/ Finally, any advice on how founders should keep up with IP law changes, especially in fast-evolving fields like AI and blockchain?

I would advise founders to stay abreast of fast changing developments by staying connected in a network focussing on their industry, as well as joining particular industry groups of interest. For example, I get updates on a daily basis from all of my LinkedIn contacts who are posting, reposting, or liking various stories of interest. For specific changes in IP law, of course you can always reach out to your favourite IP lawyer who would be happy to chat with you, hopefully off the clock until they start working on a deliverable that brings value to you and your business.

I hope you enjoyed this interview with Tai. If you’ve got any more questions, please share them in the comments and/or reach out to Tai directly via LinkedIn. I’m looking forward to doing more interviews, are there any industry experts that you’d like to hear from? Share in the comments below.

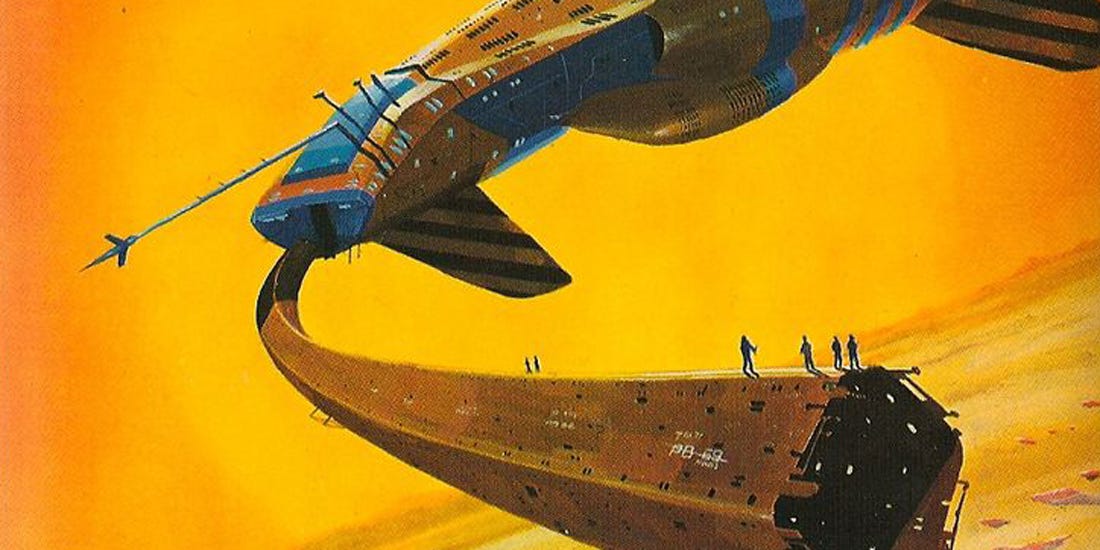

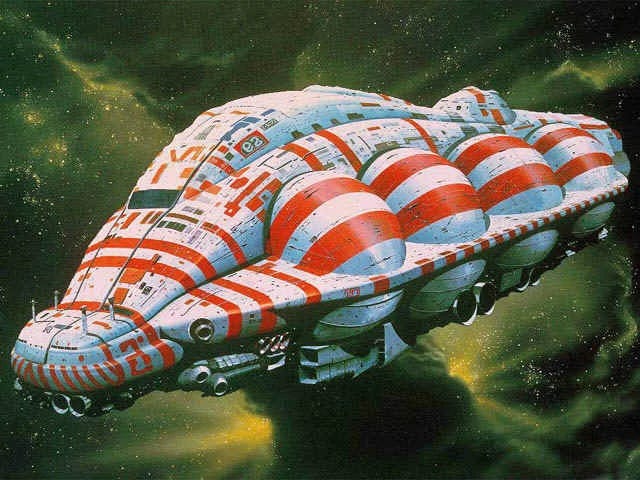

🎨 About the artist

Chris Foss, a legendary British sci-fi artist best known for his science fiction book covers. He’s considered the face of retrofuturistic spaceship art.