We'll Always Be Designing Chairs

On human restlessness, and why AGI won't be the last word

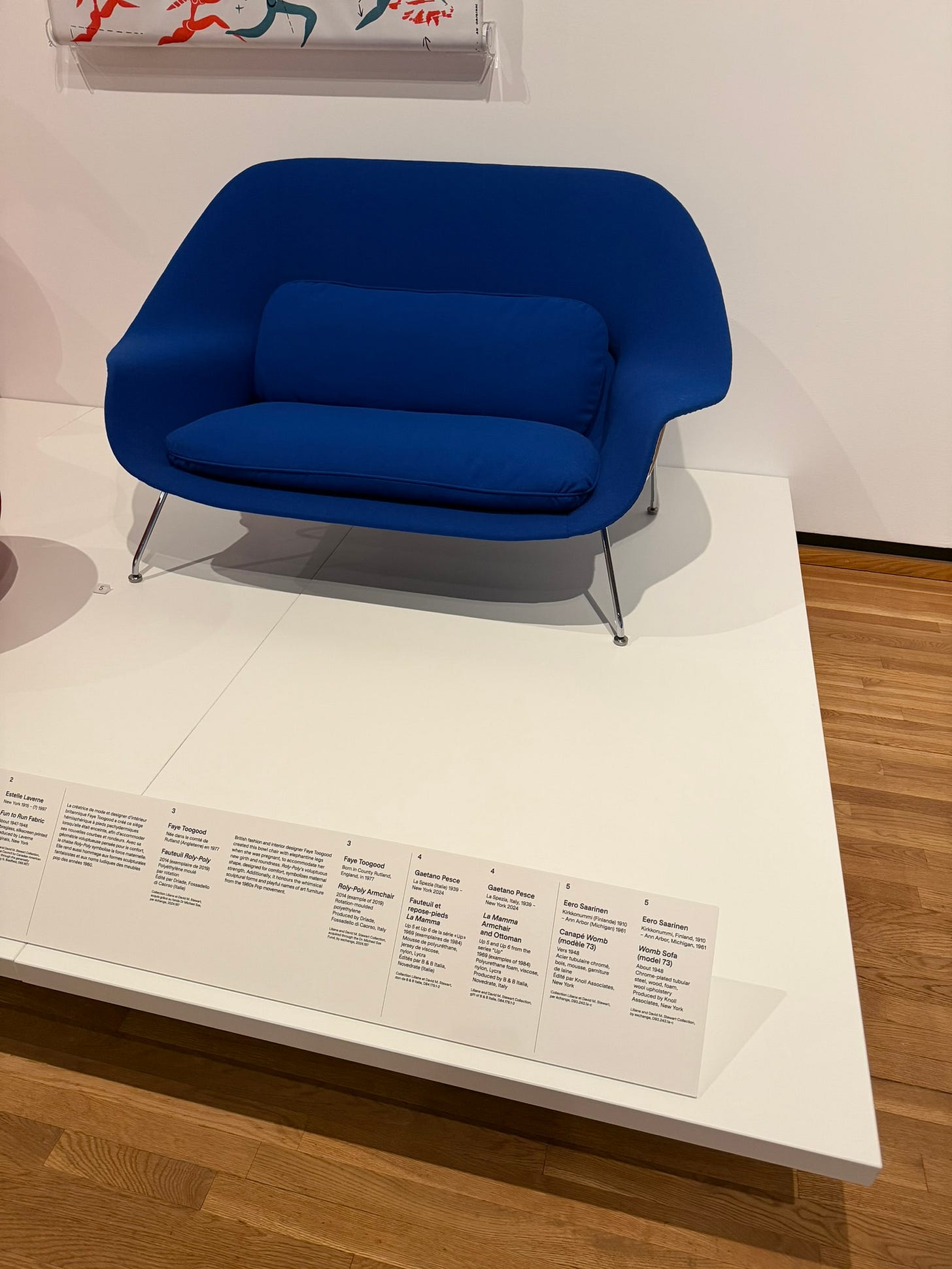

There’s an exhibit at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts right now that stopped me in my tracks.

Chairs. Hundreds of them. Spanning centuries of design, laid out like a visual argument for something I couldn’t quite articulate in the moment.

A Windsor chair from the 1700s. Thonet’s bent beech bentwood. Eames molded plywood. Verner Panton’s single-piece plastic S-curve. Chairs made from steel, rope, recycled materials, algorithms. Chairs designed for posture, for status, for a particular living room in a particular decade. Chairs so uncomfortable they were clearly never meant to be sat in.

And I kept thinking: why are we still doing this?

We solved the chair. You need something to sit on. Four legs, a seat, maybe a back. Done. Problem solved centuries ago.

Except we never stopped.

Every generation redesigns the chair from scratch. New materials arrive and designers reach for them immediately. Cultural attitudes shift, toward minimalism, toward maximalism, toward sustainability, toward spectacle, and the chair shifts with them. Ergonomics becomes a field and suddenly the chair is a medical device. The home office becomes a thing and suddenly we need an entirely new category of chair. A new generation of designers decides everything that came before was wrong, starts over, and produces something that makes the previous generation uncomfortable in every sense.

The chair is never finished. Not because it’s broken. Because we’re not.

Humans are in a perpetual state of discontent and curiosity. We don’t optimize and then stop. We optimize, get comfortable with the solution, and then immediately start wondering if the solution was the right question. It’s not a flaw in our thinking. It’s the mechanism of how we think.

I keep hearing a version of the same fear about AI: if AGI can do this, what’s left for us?

It’s a reasonable thing to wonder. If a sufficiently powerful system can produce better design, better writing, better research than any individual human, what does the human add?

The chair answers this.

We didn’t stop designing chairs when mass manufacturing made them cheap and available to everyone. We didn’t stop when ergonomics research told us exactly what the “optimal” seated position was. We won’t stop when AI can generate ten thousand chair variations in the time it takes a human designer to sketch one.

Because the chair was never purely about the chair. It’s about the conversation a designer is having with the culture they live in. It’s about the material someone discovered last year that suggests a new form. It’s about a reaction against what came before, a new idea about what a home should feel like, a problem that didn’t exist until five minutes ago.

AGI doesn’t end that conversation. Nothing ends that conversation. It’s not a problem to be solved. It’s an expression of what we are.

The things we keep returning to, the things we never declare finished, are the ones that carry human meaning. Not just utility. Meaning. The chair has to sit right and look right and feel like it belongs in this moment, in this room, to this person. That’s not a specification you can freeze. It evolves because we evolve.

The fear of AI replacing human creativity assumes creativity is a function being performed. Something with inputs and outputs that a better system could run more efficiently.

But standing in that museum, looking at a hundred years of chairs that were each, in their moment, a definitive statement about what a chair should be, I don’t think that’s what’s happening. What I was looking at was evidence of something relentless and unresolvable in us. The drive to keep asking the question, even after you’ve answered it.

That doesn’t go away with better tools. It goes faster.

We’ll still be designing chairs in fifty years. They’ll look nothing like what we have now. Some of them will be made with AI, some of them will be made in reaction to AI, some of them will be made by designers who can’t explain why they made the choices they made except that it felt right.

And someone, somewhere, will be standing in a museum looking at all of them, wondering the same thing I wondered.

Why are we still doing this?

And the answer will still be: because we can’t help it. Because that’s the point.